Women of the 1916 Easter Rising

|

This week, as Catholics, we celebrate the Holiest of Holy Days.

Let us also take a moment to remember 1916 and commemorate those who gave their lives for Irish Unity, Independence, and Sovereignty. Did you know: The Easter Lily tradition began in 1926 with the Cumann na mBan (Women's Association) to honor the sacrifice of the men and women of the 1916 Rising and raise funds for Republican prisoners' dependents Did you know: Traditionally, they were sold outside church gates on Easter Sunday Did you know: The lily's colors (green, white, and orange) are seen as symbolic of the Irish flag, representing the unity between different traditions within the Irish nation |

Women's Museum of Ireland | https://www.womensmuseumofireland.ie/

Easter Rising Stories | https://www.facebook.com/EasterRisingStories

Dublin 1916 - 1923 Then & Now | https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100067403499307

Easter Rising Stories | https://www.facebook.com/EasterRisingStories

Dublin 1916 - 1923 Then & Now | https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100067403499307

Cumann na mBan 'The Women's Council' but in English termed The Irishwomen's Council),[1] abbreviated C na mB,[2] is an Irish republican women's paramilitary organisation formed in Dublin on 2 April 1914, merging with and dissolving Inghinidhe na hÉireann, and in 1916, it became an auxiliary of the Irish Volunteers.[3] Although it was otherwise an independent organisation, its executive was subordinate to that of the Irish Volunteers, and later, the Irish Republican Army.

Cumann na mBan was active in the War of Independence and took the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War. Cumann na mBan was declared an illegal organisation by the government of the Irish Free State in 1923. This was reversed when Fianna Fáil came to power in 1932.

During the splits in the republican movement of the later part of the 20th century, Fianna Éireann and Cumann na mBan supported Provisional Sinn Féin in 1969 and Republican Sinn Féin in 1986.

Cumann na mBan was active in the War of Independence and took the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War. Cumann na mBan was declared an illegal organisation by the government of the Irish Free State in 1923. This was reversed when Fianna Fáil came to power in 1932.

During the splits in the republican movement of the later part of the 20th century, Fianna Éireann and Cumann na mBan supported Provisional Sinn Féin in 1969 and Republican Sinn Féin in 1986.

Margaret Buckley | Dr. Ada English | Countess Markievicz | Dorothy MacArdle | Marie Perolz| Mary MacSwiney | Rosie Hackett | Madge Daly | Margaret Skinnider | Christy Crothers | May Gibney | Josephine ‘Min’ Ryan| Susan Mitchell | Máire Aoife Comerford | Molly Childers

Brigid Lyons Thornton describing Easter Saturday 1916.

In the summer of 1915, Brigid was staying with an aunt and uncle in Dublin when she joined the ‘Cumann na mBan’, of which her aunt was a prominent officer. Brigid learned first aid and when a prominent nationalist Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa died in New York, she was picked to head the Cumann na mBan section of his funeral parade when he was buried in Dublin.

Brigid settled into her new life as a medical student at University College Galway and began to get involved in more serious nationalist activities; aiding the escape of prisoners, handing over guns and organising a Cumann na mBan branch in Galway. All this would be in preparation for her role in the Easter Rising in 1916. Brigid was at home in Longford in Easter of 1916 when word spread that many members of the Irish Volunteer Force had taken over strategic buildings in Dublin with the British Army returning fire and that an uprising was taking place. Along with her Uncle and a few others she headed to Dublin to see how she could be of service.

After arriving in Dublin, Brigid was ushered to the Four Courts, where some of the fiercest fighting took place. Due to her medical training and background, Brigid was given the task of nursing the wounded and also serving up provisions to the exhausted fighters. As Brigid was brave and courageous throughout her involvement in the Easter Rising, she was the recipient of gold sovereigns that she stitched into her dress in case of arrest.

When Padraig Pearse surrendered to the British army on the 29th of April, Brigid and some fellow nurses were arrested and taken to Richmond Barracks (later Keogh Barracks). The nurses were under arrest for several days, during which time some of the leaders of the Easter rising were found guilty and shot. Eventually Brigid was released. However she was a changed woman. She knew now that only a government in Dublin, ruled by and for the people, would be the answer to Ireland’s problems.

In the following years of Home Rule and WW1, Brigid became more and more involved with the nationalist movement; smuggling money, gold and guns to fund the ‘cause’. She and her fellow Cumann na mBan women kept “morale high…. With parcels, protests and letters.” Brigid was one of the most active Cumann na mBan women, from sending parcels to writing to prisoners. She did this while also continuing her studies.

After the establishment of an Irish Republic finally came in 1922, Brigid became the only female to ever be commissioned as an officer in the new Irish Army. She later went on to become a leading figure in the fight against tuberculosis amongst the poor in Ireland, carrying out research in Nice and Switzerland, and pioneering the ‘BCG’ vaccination scheme in the 1950s, practically ridding Ireland of tuberculosis. Brigid’s role in these diverse, traditionally male-dominated fields certainly was extraordinary, even daring, for a time when women were to be seen and not heard.

Dr. Brigid died aged 91 and was interred on Easter Monday 1987 in Toomore graveyard, with full military honours.

Rachel Sayers

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=959005062934115&set=pb.100064738900976.-2207520000&type=3

During 1916, Chris Caffrey of Cumann na mBan was trying to deliver a message when she was stopped and questioned by the British. When her interrogators detained her, she quickly popped the note into her mouth and began chewing. When asked what she was eating, she offered them sweets from her pocket. She barely escaped and only the candy in her pocket saved her. It did not keep her from being “thoroughly” searched before they let her go. Margaret Skinnider also mentions her in her book “Doing My Bit For Ireland.”

Photo of Chris Caffrey wedding photo.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=938032661698022&set=pb.100064738900976.-2207520000&type=3

Photo of Chris Caffrey wedding photo.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=938032661698022&set=pb.100064738900976.-2207520000&type=3

Kathleen Boland describing some of the gun smuggling activities at 64 Middle Abbey Street, Dublin in her witness statement during the War of Independence around 1920. Her brothers Gerald, Harry and Edmund were all in the national movement and IRB.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=898587368975885&set=pb.100064738900976.-2207520000&type=3

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=898587368975885&set=pb.100064738900976.-2207520000&type=3

Helena Molony on recounting her time in 1916: ‘When we walked out that Easter Monday morning we felt in a very real sense that we were walking with Ireland into the sun’. The quote in the picture looks at the role of women at the time during the 1916 period. She was an Irish republican, feminist and labour activist. As well as the 1916 Easter Rising Helena later became the second woman president of the Irish Trade Union Congress.

https://

www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=813070444194245&set=pb.100064738900976.-2207520000&type=3

https://

www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=813070444194245&set=pb.100064738900976.-2207520000&type=3

The monthly Shan Van Vocht magazine helped reawaken Irish patriot spirit twenty years before the 1916 Easter Rising. It was set up in 1896 by two Belfast women, Alice Milligan and Anna Johnston. It was important during the centenary commemorations of the 1798 Rebellion. Alice Milligan would sometimes write under the pseudonym Iris Olkryn and Anna Johnston would write under the name Ethna Carbery.

The paper pulled together in its articles many aspects of life in Ireland – cultural, social, political and historical – and its approach was from within the cultural/nationalist/separatist camp, drawing inspiration from Wolfe Tone, James Fintan Lalor and John Mitchel. It provided a platform for writers such as James Connolly, although in his case the editors disassociated themselves from his socialism, and for Douglas Hyde and Arthur Griffith and many others. It also provided a valuable outlet for women writers, and it publicised women’s groups and their campaigns and views.

The Shan Van Vocht subscriber list was transferred to Arthur Griffith’s United Irishman newspaper in 1899 when it ceased publication.

The newspapers are digitized and can be read in full at the following link. https://digital.ucd.ie/view/ucdlib:43116

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=645835437584414&set=pb.100064738900976.-2207520000&type=3

The paper pulled together in its articles many aspects of life in Ireland – cultural, social, political and historical – and its approach was from within the cultural/nationalist/separatist camp, drawing inspiration from Wolfe Tone, James Fintan Lalor and John Mitchel. It provided a platform for writers such as James Connolly, although in his case the editors disassociated themselves from his socialism, and for Douglas Hyde and Arthur Griffith and many others. It also provided a valuable outlet for women writers, and it publicised women’s groups and their campaigns and views.

The Shan Van Vocht subscriber list was transferred to Arthur Griffith’s United Irishman newspaper in 1899 when it ceased publication.

The newspapers are digitized and can be read in full at the following link. https://digital.ucd.ie/view/ucdlib:43116

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=645835437584414&set=pb.100064738900976.-2207520000&type=3

Dr Kathleen Lynn discussing some of the preparations she was involved in before the 1916 Rising

https://www.facebook.com/EasterRisingStories/photos/pb.100064738900976.-2207520000/3204908153085948/?type=3

https://www.facebook.com/EasterRisingStories/photos/pb.100064738900976.-2207520000/3204908153085948/?type=3

Mary "Mamie" Kilmartin mentions how the Father Matthew Hall was used as a hospital to treat the wounded during Easter week. The Hall is near both the Four Courts and North King Street. She carried out first aid in battles around the Four Courts. She joined the Colmcille Branch of Cumann na mBan In 1915. Her older brother Paddy also served as a Volunteer in D Company 1st Battalion. She married Patrick Stephenson in September 1917, who had fought in the Mendicity Institute and GPO garrisons during Easter week.

https://www.facebook.com/EasterRisingStories/photos/pb.100064738900976.-2207520000/3200079173568846/?type=3

https://www.facebook.com/EasterRisingStories/photos/pb.100064738900976.-2207520000/3200079173568846/?type=3

Alice Stopford Green was an Irish historian and nationalist originally from Meath Before moving to London. She was vocal in her opposition to England's colonial policy in South Africa during the Boer Wars and supported Roger Casement who highlighted the atrocities inflicted in The Congo. She had tried to make the idea of Home Rule more attractive to Ulster Unionists and was closely involved in the Howth gun running. She was one of the first nominees to the newly formed Seanad in 1922 until her death in 1929.

https://www.facebook.com/EasterRisingStories/photos/pb.100064738900976.-2207520000/3103438219899609/?type=3

https://www.facebook.com/EasterRisingStories/photos/pb.100064738900976.-2207520000/3103438219899609/?type=3

Maud Gonne's advice to Irish women on serving their country before all else. Inghinidhe na hÉireann "Daughters of Ireland" was a radical Irish nationalist women's organisation led by Maud Gonne from 1900 to 1914, when it merged with the newly formed Cumann na mBan.

https://www.facebook.com/EasterRisingStories/photos/pb.100064738900976.-2207520000/3025050841071681/?type=3

https://www.facebook.com/EasterRisingStories/photos/pb.100064738900976.-2207520000/3025050841071681/?type=3

|

Margaret Buckley, as well as a majority of Cumann na mBan were opposed to the Treaty. She had been active in nationalist and trade union circles and had served as a judge in the Dáil Courts in Dublin North during the 1919-21 War of Independence. She had been interned in Mountjoy in January 1923 during the Irish Civil War. She was in the “Suffolk Street” cell. The Deputy Governor of the prison in charge of the women, Paudeen O’Keefe was a former secretary of Sinn Fein which Buckley had worked under. The “Suffolk Street” female prisoners supported a more “militant state” during their incarceration.

|

O’Keefe had already given concessions such as ingredients for pancakes on Shrove Tuesday as well as a gas stove. Tensions escalated in the prison due to overcrowding. Beds were thrown from the landing and cells were damaged. Free State soldiers fired blank shots at the women. Furniture was removed and as a result Buckley and others went on hunger strike until the furniture was returned. It was successful and other concessions were granted.

During her imprisonment, she was elected Officer Commanding (OC) of the republican prisoners in Mountjoy, Quartermaster (QM) in the North Dublin Union and OC of B-Wing in Kilmainham. She was an active member of the Women Prisoners' Defence League, founded by Maud Gonne and Charlotte Despard in 1922. She was released in October 1923. Buckley in later years would make history by becoming the first female leader of a political organization becoming president of Sinn Fein in 1937. The following year she published her prison memoir “The Jangle of the Keys” which chronicled her time in various prisons during the Civil War. She points out in one of the quotes below how as prisoners they would have to stand together like a phalanx to get what they hoped to achieve Easter Rising Stories June 23, 2021 |

|

Dr. Ada English, 4th January 1922, Treaty Debates, Dáil Éireann. “A Chinn Chomhairle is a lucht na Dála, níl mórán agam le rá ach dearfa mé cúpla focal. A Deputy who spoke in favour of the Treaty wanted to know why the young men should be sent to the shambles—I think that was the word he used. I should be sorry to see young men or old men, or women, or children going to the shambles, but when there is a question of right or wrong in it I would be prepared to go to the shambles myself, and I do not see why everybody would not. I credit the supporters of the Treaty with being as honest as I am, but I have a sound objection to it. I think it is wrong; I have various reasons for objecting to it, but the main one is that, in my opinion, it was wrong against Ireland, and a sin against Ireland. I do not like talking here about oaths. I have heard about oaths until my soul is sick of them, but if this Treaty were forced on us by England—as it is being forced—and that paragraph 4, the one with the oath in it were omitted, we could accept it under force; but certainly, while those oaths are in it, oaths in which we are asked to accept the King of England as head of the Irish State, and we are asked to accept the status of British citizens—British subjects—that we cannot accept. As far as I see the whole fight in this country for centuries has centred round that very point. We are now asked not only to acknowledge the King of England's claim to be King of Ireland, but we are asked to swear allegiance and fidelity ("No! no!") in virtue of that claim. Perhaps not, but that is the way I read it. For the last seven hundred centuries, roughly (laughter)—I mean seven centuries— time does seem to be long here (laughter). However a jolly long time, anyway, Ireland has been fighting England and, as I understood it, the grounds of this fight always were that we denied the right of England's King to this country ("No! no!"). And we denied we were British subjects. We are now asked not only to acknowledge the claims of the English King to be head of Ireland, and to acknowledge ourselves as British subjects, but we are asked to give him a right to legalise his claim by giving him a right, by our votes, to the position—that is, as far as we could give him the right. We cannot—nobody can—give him a right to the country, or the votes of anybody give him a claim. It seems to me that the taking of those oaths is a complete surrender of our claims. It is a moral surrender. It is giving up the independence of our country, and that is the main reason why I object to this Treaty. I deny that we are a possession of the British and this Treaty simply makes us one of the British possessions. Various Deputies have said that we surrendered the Republic as soon as we began to discuss any association with England. I cannot understand that position. It is not surrender of the Republic —any arrangement for association with any other country, whether England, or Germany, or Japan, or any country in the world. That did not give away the Republic in the slightest degree. That we gave up the position of an isolated Republic without alliance, with England or otherwise, might be claimed, but certainly we did not compromise in any way our claim to a Republic. We would negotiate association with England but there was no compromise in it, and I am sorry Dr. MacCartan is not here, because in his amazing speech he said he knew the Republic was being killed the moment we began to discuss association. It was his duty, and the duty of any man who thinks as he did then to stand up and tell us that, in ignorance or innocence, we were trying to murder the Republic and kill it; it is not when he sees the Republic dead. Why did he not warn us in the beginning if he thought so? I hold that the Republic is not dead, and will not die, in spite of Lloyd George and the other evil spirits who wander through the world (laughter and cheers). We are told that the country is for this Treaty—it has been told to us in various forms of words, in various ways. The country is not for this Treaty, the country is out for peace. The country wants peace and desires peace. So do we. We all want peace, but we want a peace which will be a real peace and a lasting peace and a peace based on honour and on friendship and a peace which we can keep, a peace that we can put our names to and stand by. That is the sort of peace the country wants, and it is only because the country is misled into believing that this Treaty gives such a peace that the country wants it. The country wants no peace which gives away the independence of Ireland and destroys the Republic which has been established by the will of the Irish people (hear, hear). We have had painted for us in various lurid colours the terrors of war and the desire of the people for quietness and peace. Well, peace is a good thing, but in the days of the famine the people were also told that they should be peaceful and submissive and quiet, and accept what the English chose to give them—the rotten potatoes—and let the corn and food be exported out of the country. There were people then, Republicans and Revolutionists, who encouraged the people to fight for the country in spite of the men with the streak, and free themselves and keep the food in the country. But some of the influences that are working against the country to-day were working against it then and advised peace. They got peace—and death and famine. You can lose more men—their bodies as well as their souls—by an ignoble peace than by fighting for just rights (cheers). The evacuation of the English troops is one of the things that are being held up to us as being one of the very good points in the Treaty. |

It would be a very desirable thing, indeed, that the English troops evacuated this country, if they did evacuate it, but I hold that Ulster is still part of Ireland and I have not heard a promise that the British troops are to evacuate Ulster. They are still there. I understand they are to be drawn from the rest of Ireland and, as I read the Treaty, there is not one word of promise in it about the evacuation of the British troops. There was, I think, a letter read from the man across—Lloyd George—promising that evacuation would begin in some certain time, but I should like to know was that promise part of the arrangement made between the British Government on one hand, and the plenipotentiaries of the Irish Republic on the other, or was it merely a private arrangement of Mr. Lloyd George? I suppose that the English Government believe—if they were going, even to a slight degree, to evacuate the country, it is probably because they thought that the country would be held for them by the Free State troops. They are depending on the acceptance of the Treaty. If this Treaty is going to be kept are we to understand that the Free State will hold the country for England instead of the British Garrison? I have heard, I have listened very carefully—I think this afternoon was the first time I missed any of the speeches from the beginning, on the 14th December—to those speeches in favour of the Treaty. I have listened most carefully and attentively to see if I could find any way in which I could reconcile my conscience to vote for the Treaty. My position is not the same as when I came to Dublin. I came up opposed to the Treaty. I am ten times more opposed to it since I have heard the speeches in favour of the Treaty in this Dáil. We repudiate the Republic if this Treaty is passed; we repudiate it absolutely. It is a complete surrender and we don't get peace by it, but we get the certainty of a bitter split and division in this country; because we who stand for the complete freedom—for the separatist idea—for the complete freedom and independence of Ireland cannot sit down with our hands across. We will work and fight for it, and so there is bound to be a split. The only chance you could have of unity is by having the whole Dáil unanimously reject this thing. Then you would have the country behind you. Unity is a good thing and I am very sorry to see the unity which was in this Dáil broken up as it is at present, but I would be very much more sorry to see the Dáil united in approving of this Treaty, because unity in wrong-doing is no advantage to the country or the cause (hear, hear). What we have got in this Treaty—the material point, I suppose—is a truncated form of Dominion Home Rule for three-quarters of the country. If Dominion Home Rule were the thing we were fighting for and are satisfied to get—as those in favour of the Treaty seem to think—why, in God's name, did they not tell us that two years ago and not send out all the fellows to fight and lose their lives for a thing they did not want? On what authority did they send out, if the Republic did not exist and was not in being, any poor fellows to shoot and kill any man of any nation? If it was not for the Government of the Republic and the army why did they go out? There has been talk about compromise—that we compromised the position. I think that is a most unworthy thing to say—a most unworthy thing to say. We had lots of things to bargain about—you had lots of material things to bargain about —questions of trade and commerce and finance and the use of ports; but nobody ever suspected we were going to compromise on the question of independence and the rights of the country. Mr. MacGarry mentioned yesterday Land Acts taken in the past from England. There was no Republic in Ireland when we took the Land Acts from England. That makes a very great difference. And the Republic exists. You can take any Act you like that is consistent with the Republic, but you cannot take anything which gives away the Republic. It is not in your power to give it away. I have been asked by several people in the Dáil and elsewhere as to what views my constituents took about this matter. I credit my constituents with being honest people, just as honest as I consider myself—and I consider myself fairly honest—they sent me here as a Republican Deputy to An Dáil which is, I believe, the living Republican Parliament of this country. Not only that, but when I was selected as Deputy in this place I was very much surprised and, after I got out of jail, when I was well enough to see some of my constituents, I asked them how it came they selected me, and they told me the wanted someone they could depend on to stand fast by the Republic, and who would not let Galway down against (cheers).That is what my constituents told me they wanted when they sent me here, and they have got it (cheers). This is—a Chinn Chomhairle, may I read a letter which has been received to-day from the Graduates of the National University of Ireland? It is not to me, it is to Professor Stockley. "As our representative, we have perfect confidence in your ability to represent us. We disapprove of any interference by individual graduates in the free actions of our representatives. We disapprove further of any attempt to stampede members of the Dáil to act in contradiction of their considered opinions.—M. O'Kennedy." Cúig cinn. I am only speaking about my own constituents. There is a point I want to make. I think that it was a most brave thing to-day to listen to the speech by the Deputy from Sligo in reference to the women members of An Dáil, claiming that they only have the opinions they have because they have a grievance against England, or because their men folk were killed and murdered by England's representatives in this country. It was a most unworthy thing for any man to say here. I can say this more freely because, I thank my God, I have no dead men to throw in my teeth as a reason for holding the opinions I hold. I should like to say that I think it most unfair to the women Teachtaí because Miss MacSwiney had suffered at England's hands. That, a Chinn Chomhairle is really all I want to say. I am against the Treaty, and I am very sorry to be in opposition to (nodding towards Mr. Griffith and Mr. Collins). (Cheers) |

|

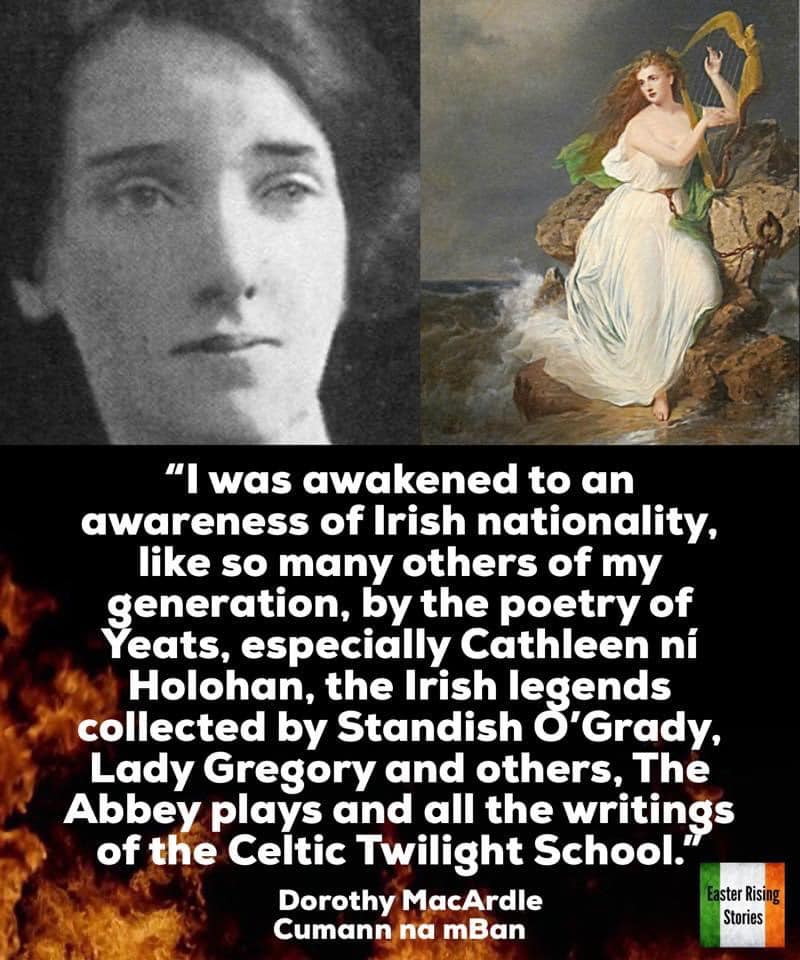

Dorothy MacArdle describes her awakening to Irish nationality from the works of WB Yeats, Standish O’Grady, Lady Gregory and the Celtic Twilight School. Her books on “The Irish Republic” and “Tragedies of Kerry” are highly regarded. The painting on the right is ‘The Harp of Erin’ by Thomas Buchanan from 1867. Ireland was often depicted as a woman, often named Cathleen Ní Houlihan in art and plays. A mural was painted to Dorothy MacArdle in Dundalk in 2020.

Easter Rising Stories June 13, 2023 |

|

Countess Markievicz’s speech about patriotism and serving Ireland to the young women of the Irish Literary Society in 1909 in Dublin. “I take it as a great compliment that so many of you, the rising young women of Ireland, who are distinguishing yourselves every day and coming more and more to the front, should give me this opportunity. We older people look to you with great hopes and a great confidence that in your gradual emancipation you are bringing fresh ideas, fresh energies and above all a great genius for sacrifice into the life of the nation.” “Now, I am not going to discuss the subtle psychological question of why it was that so few women in Ireland have been prominent in the national struggle, or try to discover how they lost in the dark ages of persecution the magnificent legacy of Maeve, Fheas, Macha and their other great fighting ancestors. True, several women distinguished themselves on the battle fields of 1798, and we have the women of the ‘Nation’ newspaper, of the ‘Ladies Land League’, also in our own day the few women who have worked their hardest in the Sinn Fein movement and in the Gaelic League and we have the women who won a battle for Ireland, by preventing a wobbly Corporation from presenting King Edward of England with a loyal address. But for the most part our women, though sincere, steadfast Nationalists at heart, have been content to remain quietly at home, and leave all the fighting and the striving to the men. “Lately things seem to be changing ….so now again a strong tide of liberty seems to be coming towards us, swelling and growing and carrying before it all the outposts that hold women enslaved and bearing them triumphantly into the life of the nation to which they belong. Easter Rising Stories December 25, 2024 |

“We are in a very difficult position here, as so many Unionist women would fain have us work together with them for the emancipation of their sex and votes – obviously to send a member to Westminster. But I would ask every nationalist woman to pause before she joined a Suffrage Society or Franchise League that did not include in the programme the Freedom of their Nation. A Free Ireland with No Sex Disabilities in her Constitution should be the motto of all Nationalist Women. And a grand motto it is.

“Women, from having till very recently stood so far removed from all politics, should be able to formulate a much clearer and more incisive view of the political situation than men. For a man from the time he is a mere lad is more or less in touch with politics, and has usually the label of some party attached to him, long before he properly understands what it really means….. “Now, here is a chance for our women……….. Fix your mind on the ideal of Ireland free, with her women enjoying the full right of citizenship in their own nation, and no one will be able to side-track you, and so make use of you to use up the energies of the nation in obtaining all sorts of concessions – concessions too, that for the most part were coming in the natural course of evolution, and were perhaps just hastened a few years by the fierce agitations to obtain them. “If the women of Ireland would organise the movement for buying Irish goods more, they might do a great deal to help their country. If they would make it the fashion to dress in Irish clothes, feed on Irish food – in fact, in this as in everything, live really Irish lives, they would be doing something great, and don’t let our clever Irish colleens test content with doing this individually, but let them go out and speak publicly about it, form leagues, of which ‘No English goods’ is the war cry….. “I daresay you will think this all very obvious and very dull, but Patriotism and Nationalism and all great things are made up of much that is obvious and dull, and much that in the beginning is small, but that will be found to lead out into fields that are broader and full of interest. You will go out into the world and get elected onto as many public bodies as possible, and by degrees through your exertions no public institution – whether hospital, workhouse, asylum, or any other and no private house – but will be supporting the industries of your country………… “To sum up in a few words what I want the Young Ireland women to remember from me. Regard yourselves as Irish, believe in yourselves as Irish, as units of a nation distinct from England………..and as determined to maintain your distinctiveness and gain your deliverance. Arm yourselves with weapons to fight your nations cause. Arm your souls with noble and free ideas. Arm your minds with the histories and memories of your country and her martyrs, her language and a knowledge of her arts, and her industries…….. “ |

|

Marie Perolz discussing the impact that the Presentation nuns made on her before 1916. She signals out Sister Bonaventure as being a particular influence in shaping her to become a rebel for Ireland, whom is also pictured below. Marie Perolz was in Cumann na mBan, the Irish Citizen Army, Inghini na hEireann and the Gaelic League and was key to reviving the Irish Women’s Workers Union in the years after 1916. She was quite close to Constance Markievicz.

Easter Rising Stories December 30, 2023 |

|

Mary MacSwiney was a member of Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland). She had also joined Conradh na Gaeilge and was one of the founding members and secretary of the Munster Women’s Franchise League. She became disillusioned with the Franchise movement of suffragettes who she believed didn’t have Ireland’s interests first and were “Britons first, suffragists second and Irish women, perhaps, a bad third”.

|

Mary was also a founding member and later president of Cork’s Cumann na mBan. She helped found Scoil Íte with a focus on Irish history. She would later join Sinn Fein after the Easter Rising. She campaigned for her brother Terence MacSwiney who famously died on hunger strike in 1920. She had travelled to the US to make them aware of conditions in Ireland with Terence’s widow Muriel.

She was a strong opposer of The Treaty, having once given a 2 hr 45 minute speech on her feelings regarding it. She was elected to the Third Dail on June 22nd 1922. She would be imprisoned during the Civil War. She went on a hunger strike that lasted 21 days. She was released and rearrested again in April 1923 on her way to the funeral of Liam Lynch. She retained her seat in 1923 but refused to take it as a result of the Oath of Allegiance. She felt that the Irish Free State was neither free, Irish or a state. Easter Rising Stories January 12, 2024 |

|

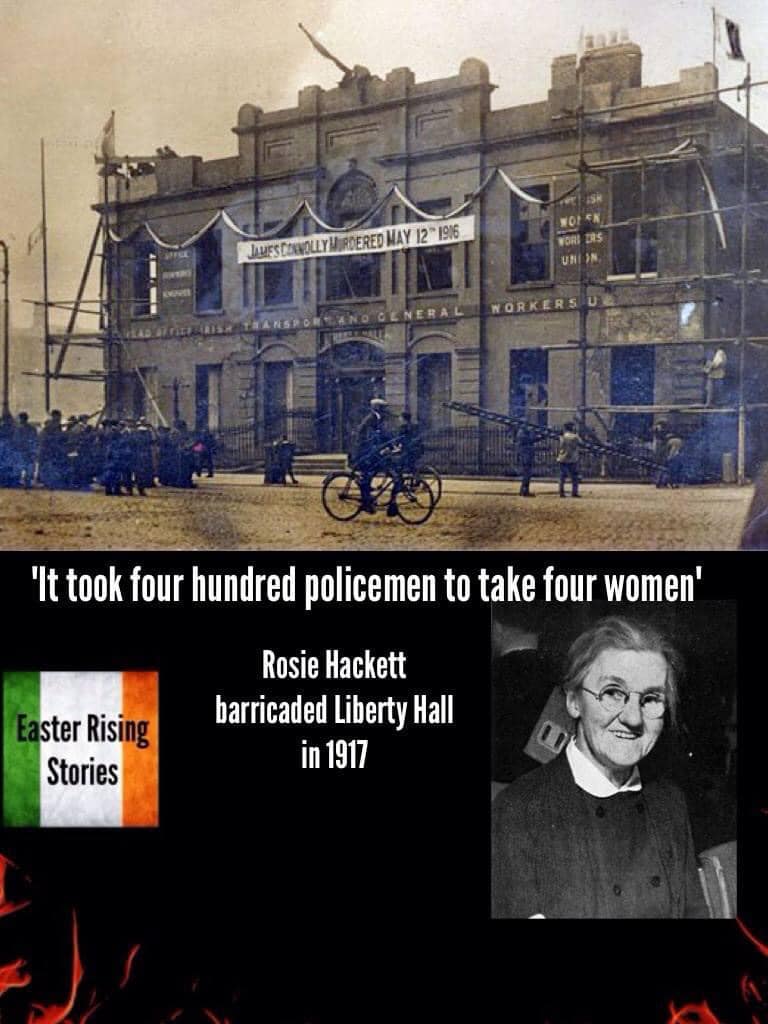

Remembering 1916 in 1917. Rosie Hackett Witness Statement 546:

“On the occasion of the first anniversary of Connolly’s death, the Transport people decided that he would be honoured. A big poster was put up on the Hall, with the words: “James Connolly Murdered, May 12th, 1916”. It was no length of time up on the Hall, when it was taken down by the police, including Johnny Barton and Dunne. |

We were very vexed over it, as we thought it should have been defended. It was barely an hour or so up, and we wanted everybody to know it was Connolly’s anniversary. Miss Molony called us together- Jinny Shanahan, Brigid Davis and myself. Miss Molony printed another script. Getting up on the roof, she put it high up, across the top parapet. We were on top of the roof for the rest of the time it was there. We barricaded the windows. I remember there was a ton of coal in one place, and it was shoved against the door in cause they would get in. Nails were put in.

Police were mobilised from everywhere, and more than four hundred of them marched across from the Store Street direction and made a square outside Liberty Hall. Thousands of people were watching from the Quay on the far side of the river. It took the police a good hour or more before they got in, and the script was there until six in the evening, before they got it down. I always felt that it was worth it, to see all the trouble the police had in getting it down. No one was arrested. Of course, if it took four hundred policemen to take four women, what would the newspapers say? We enjoyed it at the time- all the trouble they were put to. They just took the script away and we never heard any more. It was Miss Molony’s doings. Historically, Liberty Hall is the most important building that we have in the city. Yet, it is not thought of at all by most people. More things happened there, in connection with the Rising, than in any other place. It really started from there." Easter Rising Stories November 12, 2024 |

|

Madge Daly discussing the organising of Cumann na mBan in Limerick. She was a founder member of and a dominant force in Cumann na mBan in Limerick city serving from 1914 to 1924, and became the President of Cumann na mBan in Limerick, She was the driving force of the branch along with coming from a very revolutionary family.

Her father was a Fenian as was her uncle John Daly. Her brother Ned Daly was executed for his part in the Easter 1916 Rising. Her sister, Kathleen, was married to Tom Clarke, who was also executed for the 1916 Rising. Easter Rising Stories December 2, 2024 |

|

Margaret Skinnider recounts her plan to bomb a hotel during the 1916 Easter Rising as well as the near fatal injuries she received. This is an excerpt from her book “Doing My Bit For Ireland” which you can read in the web link at the bottom of this post.

“I was up-stairs, studying a map of our surroundings and trying to find a way by which we could dislodge the soldiers from the roof of the Hotel Shelbourne. When Commandant Mallin came in, I asked him if he would let me go out with one man and try to throw a bomb attached to an eight-second fuse through the hotel window. I knew there was a bow-window on the side farthest from us, which was not likely to be guarded. We could use our bicycles and get away before the bomb exploded,—that is, if we were quick enough. At any rate, it was worth trying, whatever the risk. Commandant Mallin agreed the plan was a good one, but much too dangerous. I pointed out to him that it had been my speed which had saved me so far from machine-gun fire on the hotel roof. It was not that the British were doing us any real harm in the college,but it was high time to take the aggressive, for success would hearten the men in other "forts" who were not having as safe a time of it. He finally agreed, though not at all willingly, for he did not want to let a woman run this sort of risk. My answer to that argument was that we had the same right to risk our lives as the men; that in the constitution of the Irish Republic, women were on an equality with men. For the first time in history, indeed, a constitution had been written that incorporated the principle of equal suffrage. |

But the Commandant told me there was another task to be accomplished before the hotel could be bombed. That was to cut off the retreat of a British force which had planted a machine-gun on the flat roof of University Church. It was against our rules to use any church, Protestant or Catholic, in our defense, no matter what advantage that might give us. But this church, close at hand, had been occupied by the British and was cutting us off from another command with whom it was necessary to keep in communication. In order to cut off the retreat of these soldiers, it would be necessary to burn two buildings. I asked the Commandant to let me help in this undertaking. He consented, and gave me four men to help fire one building, while another party went out to fire the other. It meant a great deal to me that he should trust me with this piece of work, and I felt elated. While I changed once more into my uniform, for the work of war can only be done by those who wear its dress, I could still hear them singing:

"Who fights for Ireland, God guide his blows home! Who dies for Ireland, God give him peace! Knowing our cause just, March we victorious, Giving our hearts' blood Ireland to free!" It took only a few moments to reach the building we were to set afire. Councilor Partridge smashed the glass door in the front of a shop that occupied the ground floor. He did it with the butt of his rifle and a flash followed. It had been discharged! I rushed past him into the doorway of the shop, calling to the others to come on. Behind me came the sound of a volley, and I fell. It was as I had on the instant divined. That flash had revealed us to the enemy. "It's all over," I muttered, as I felt myself falling. But a moment later, when I knew I was not dead, I was sure I should pull through. Before another volley could be fired, Mr. Partridge lifted and carried me into the street. There on the sidewalk lay a dark figure in a pool of blood. It was Fred Ryan, a mere lad of seventeen, who had wanted to come with us as one of the party of four. "We must take him along," I said. But it was no use; he was dead. With help, I managed to walk to the corner. Then the other man who had stopped behind to set the building afire caught up with us. Between them they succeeded in carrying me back to the College of Surgeons. As we came into the vestibule, Jo Connolly was waiting with his bicycle, ready to go out with me to bomb the hotel. His surprise at seeing me hurt was as if I had been out for a stroll upon peaceful streets and met with an accident. They laid me on a large table and cut away the coat of my fine, new uniform. I cried over that. Then they found I had been shot in three places, my right side under the arm, my right arm, and in the back on my right side. Had I not turned as I went through that shop-door to call to the others, I would have got all three bullets in my back and lungs and surely been done for. They had to probe several times to get the bullets, and all the while Madam held my hand. But the probing did not hurt as much as she expected it would. My disappointment at not being able to bomb the Hotel Shelbourne was what made me unhappy. They wanted to send me to the hospital across the Green, but I absolutely refused to go. So the men brought in a cot, and the first-aid girls bandaged me, as there was no getting a doctor that night. What really did distress me was my cough and the pain in my chest. When I tried to keep from coughing, I made a queer noise in my throat and noticed every one around me look frightened. "It's no death-rattle," I explained, and they all had to laugh,—that is, all laughed except Commandant Mallin. He said he could not forgive himself as long as he lived for having let me go out on that errand. But he did not live long, poor fellow! I tried to cheer him by pointing out that he had in reality saved my life, since the bombing plan was much more dangerous. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/52740/52740-h/52740-h.htm Easter Rising Stories December 7, 2024 |

|

Christy Crothers of the Irish Citizen Army discusses collecting ammunition and preparing munitions before the 1916 Easter Rising in Liberty Hall. An article about his involvement is in this link. He is pictured here with his wife Dina.

http://eastwallforall.ie/?p=2734 Easter Rising Stories December 17, 2024 |

|

When the 1916 Easter Rising started Gibney approached the garrison at the General Post Office and asked to join them. She knew one of the volunteers on duty and she was allowed in. She remained at the GPO for the rest of the week. She was involved in general activities, including cooking and first aid but also delivered messages to other garrisons such as the one to Michael Mallin at the Royal College of Surgeons.

When she was told to leave she and Bridget Connolly were making their way home when they were arrested and sent to Broadstone Station. However, on this occasion she was not detained for very long. She joined Cumann na mBan in September of that year and met her fiancé Dick McKee, who was later interrogated, tortured and killed at Bloody Sunday. During the War of Independence she operated as a courier for the IRA., carrying messages, hiding and moving weapons, and hid Victor Murphy, a Jacob's factory garrison member who had avoided arrest with the others. Easter Rising Stories December 18, 2024 |

|

Josephine ‘Min’ Ryan discussing the influence Arthur Griffith had on her family between the years 1902-06. She was a member of Cumann na mBan and the honorary secretary of the executive committee. She took part in 1916 Easter Rising and War of Independence. She was engaged to Seán MacDiaramada and later on married Richard Mulcahy.

Easter Rising December 30, 2024 |

|

Susan Mitchell was a pacifist, writer and critic who was sympathetic to the leaders in the Rising of 1916. She had found herself near the fighting at Portobello Barracks during Easter week. She had written in May to her brother “I still feel as if it was a nightmare -only the ruins of Dublin prove it to be no dream.” She was close to the Yeats family and AE Russell.

Easter Rising Stories December 30, 2024 |

|

Máire Comerford’s of Cuman na mBan’s new memoir describes how in her view, Molly Childers had more influence in the background of events than any other woman in Irish history.

Mary Alden Osgood Childers MBE (1875 – 1964) was an American-born Irish writer and Irish nationalist. She was the daughter of Dr. Hamilton Osgood and Margaret Cushing Osgood of Beacon Hill, Boston, Massachusetts. Molly married the writer and Irish nationalist, Erskine Childers. Their son, Erskine Hamilton Childers, became the fourth President of Ireland. She was central to the July 1914 Irish Volunteers Howth gun-running on her and her husband's yacht Asgard. A photograph taken at the time with fellow-sailor Mary Spring Rice shows her beside the rifles and ammunition boxes. During World War I, Molly was involved in politically difficult work with the Committee for Relief in Belgium. Due to the changing diplomatic situation with Germany during 1915–1918, the Belgian wartime refugees displaced by the conflict were at the centre of a cross-channel tug-of-war over the supply of desperately needed aid. Molly raised funds for them alongside her sister and mother. In January 1918, King George V conferred an MBE on her for this work. She was also awarded the Médaille de la Reine Elisabeth from Queen Elisabeth of Belgium. She and her husband Erskine Childers were members of the Irish White Cross Society, which existed before the Irish Red Cross, she as a trustee, and he as a member of its executive committee.Activist Maud Gonne was also a member of this organisation. From 1916 to 1918, Molly was honorary secretary of the Chelsea War Refugees Fund. After the Great War, in 1920, she joined the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), one of the world's oldest peace organisations, later to be merged into the UNESCO of the United Nations. Easter Rising Stories January 22, 2025 |